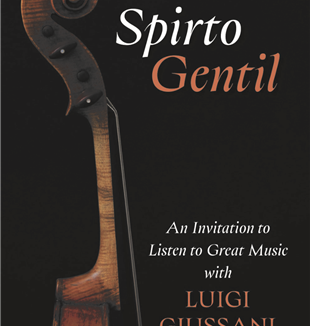

Spirto Gentil: The Heart as the Key to Music

An interview with Pier Paolo Bellini on the new publication of Fr. Luigi Giussani’s Spirto Gentil reflectionsThe discovery of Spirto Gentil gives me courage to play the music that I love with renewed insight and spiritual strength.

–Kuok-Wai Lio, pianist

Pier Paolo Bellini is associate professor at the University of Molise where he teaches Sociology of Communication in the Department of Humanities, Social Sciences, and Education. He is the general editor of the Spirto Gentil musical collection by Fr. Luigi Giussani. These reflections about various pieces of music have been collected into an edition published this year by Slant Books, Spirto Gentil: An Invitation to Listen to Great Music with Luigi Giussani. Works promoted include those of many of the great composers of the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, masterpieces of Church music, and collections of folk songs from various national traditions.

Pier Paolo, how and when were Fr. Luigi Giussani’s Spirto Gentil reflections initiated?

The idea of Spirto Gentil was born almost by chance. In 1992, we wanted to give a 70th birthday gift to Fr. Giussani – an album of Russian folk songs, which was hard to find at that time. He loved this music very much, because in those songs he saw the community dimension described as an essential factor in the development and expression of the person. Giussani used art to educate our hearts, especially books and music. His guides to works of literature – called “Books of the Christian Spirit,” that included authors such as Chesterton, Dostoyevsky, and many others – were already underway, and inspired us, while seeking out these Russian works, to consider doing the same with music.

What was the first music commentary, and how did the list grow?

It was a while before we could reproduce the Russian folk songs with a commentary, so the series itself started in 1997 with Stabat Mater by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi and Franz Schubert's Symphony No. 8 (the “Unfinished”). The series took shape according to specific music that Giussani chose in order to address those topics that were dear to him, as he sought to educate the people around him. The order that these commentaries appear in the book is under these categories: The Great Masters, Moments in the History of the Church, and A People Sings (folk music).

How did you become the curator of this series?

I am a composer. My friend, Enzo Piccinini, with Fr. Giussani, asked me to guide this collection, because I was part of Communion and Liberation and I had a degree in composition, and I was myself working with students as a teacher at the university in Milan. Production of the series ended with the death of Fr. Giussani in 2005. We did four CDs per year, which resulted in a total of 54 works.

How was this work useful to you? What did you learn?

For me it was like a second school, because while at the Conservatory I learned the technique and the musical language, with Fr. Giussani I learned to use the heart – the deepest dimension of the human being – as a key to reading the great works of tradition. The heart is what allows one to understand the contents of any language.

Why would you recommend this book to us today?

Normally, music is discussed and explained only on a very technical level. I have noticed that my colleagues in the music industry do not have the courage to say anything specific about a piece, unless it is technical. They are limited by this formalism, and they won’t go beyond it. Fr. Giussani’s way of listening to music is totally original, and more inviting to potential audiences. His analyses are comprehensible to the old and young alike, musicians and not, and he would address the work of any kind of artist, as well. His unique approach had to do with his particular way of seeing the genius within the human person. He compared his own heart with that of the artist, and invited us to do the same. With this series, he is able to help each person to understand more deeply the artist as well as himself, through the music, by comparing everything to the heart. Giussani considered music a privileged way of perceiving beauty as a splendor of the Truth – a way that the Mystery speaks to the heart of man.

Can you give some examples?

For example, in Chopin's Raindrop Prelude, Giussani hears in a single, repeated note, the urgent thirst for happiness. This is something that will never be satisfied; it is a structural demand that resounds ceaselessly in every move we make. Beethoven's VII Symphony provides another example. The first movement describes in music a celebratory party atmosphere, but in the second movement, he traces a profound and painful reflection that occurs every time the illusion of having found happiness proves to be a failure.

How is this book being received in Italy?

Universal Music (who produced about 70% of the series of CDs) wants to give the Golden LP Prize to Fr. Giussani for this book. Although classical music is no longer popular and sales were almost non-existent, classical sales have spiked up dramatically because of the book. Such numbers have never been seen in classical sales before!