The Highest Form of Culture

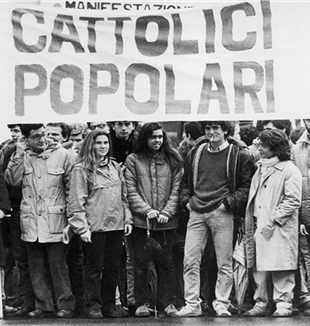

Lele Colombo's paper from the National Assembly presentation on Fr. Giussani and politicsAt the 2024 National Assembly in Estes Park, CO, Lele Colombo gave a presentation on Fr. Luigi Giussani and politics within this historical context of Communion and Liberation from 1945-2000. Below is an excerpt from the paper, "The Highest Form of Politics", generated by that presentation. The entire paper can be accessed via the PDF linked below.

In 1987, Fr. Luigi Giussani, founder of the Movement of Communion and Liberation, was invited to speak at a regional congress of one of the most influential political parties in Italy: the Christian Democrats (Democrazia Cristiana). The invitation came as a surprise to many, including Fr. Giussani himself. For years, influential lay and clerical leaders in the Italian Catholic world had objected to Giussani’s approach to politics, but by 1987, it was undeniable that he and the Movement had made a crucial contribution to the political life of the country. In his speech, Giussani succinctly defined his understanding of politics and political activity: “As the highest form of culture,” he explained, “politics must inevitably consider the person to be its fundamental concern.”

This definition of politics as the noblest of human activities, driven by concern for human flourishing, stands in stark contrast to the cynicism and frustration with which politics and political activity are often associated in contemporary North America. We might wonder if Fr. Giussani was misguided or naïve when he dubbed politics “the highest form of culture.” In order to assess the claim, however, we would do well to try to understand how he came to formulate it.

In this text, we will consider several formative events in the life of Fr. Giussani (and, by extension, of Communion and Liberation) that occurred between 1950 and 2000. In a fifty-year period that was marked by significant social, political, cultural, and religious upheaval in Italy and the world at large, Fr. Giussani was driven to ask the following questions: What is the task of the Christian in civil society? To what extent should a Christian be involved in politics? For that matter, what, if any, is the connection between politics and faith?