“I will die from having lived”

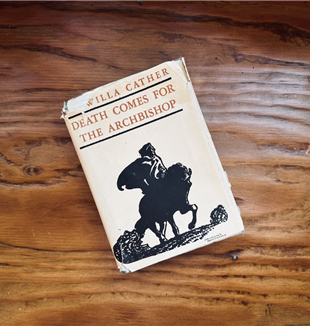

An introduction to the Book of the Month for December: Death Comes for the ArchbishopI first met Fr. Jean Latour and Fr. Joseph Vaillant, the protagonists of Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop, in 2014 after picking up a copy at a used bookstore in Memphis, TN. I had just arrived in the city as a newlywed after having met Communion and Liberation in Washington, DC, and, as I read, I felt a great familiarity with these two French missionary priests. The familiarity did not come from having anything in common – I am from Arkansas, not France; I was raised Protestant, not Catholic; I am a married woman, not a priest. Rather, the familiarity came from the perception that my recent encounter with CL was wrapped up in an experience with people who lived – and live – something quite similar to what unfolded in the lives of Fr. Joseph and Fr. Jean. I felt that I had met those same missionary fathers, though with different faces and from different countries. I had met people who followed a call to come here for me, without even knowing me.

Death Comes for the Archbishop is based on the historical figures of Jean-Baptiste Lamy and Joseph Machebeuf, and while Willa Cather was not herself Catholic, she had a remarkable way of illustrating the Church and the life of faith as if she experienced it from the inside. Cather’s Archbishop, Fr. Jean Latour, and his vicar, Fr. Joseph Vaillant, are two French priests sent from their first mission in Ohio to take care of and set in order the diocese in Santa Fe, New Mexico which had just become part of the U.S. Territory. Given the novel’s title, it is no spoiler to share that Bishop Latour dies at the end of the book in the cathedral he built, but perhaps it is a surprise to share that his dying is not ultimately the point. His death, which unfolds over the last pages, allows him (and the reader) to “live over his life”. Speaking to a confrere close to his death, Bishop Latour says, “I will not die from a cold. I will die from having lived.” We ask the Virgin Mary to pray for us “now” and “at the hour of our death” – these being the two moments we meet God – and the hour of his death is a reverberation of the great trajectory of his life, of the many ‘yeses’ given in the ‘now’, that we read about through the course of the novel.

Perfect literary witnesses of being (literally!) sent by someone, to someone, and with someone, Fr. Jean and Fr. Joseph first ride into Santa Fe, “claiming it for the glory of God,” and four pages later they meet the native Mexican people and realize that these people had “all they needed to make them happy.” These initial steps of awareness reveal the tension between living the certainty that what one brings is essential and needed, and understanding that there is something to discover and love in the place one has been sent. Cather’s protagonists show us the surprise of realizing that the place where they are called is worth knowing and loving for its own sake. When Fr. Joseph, recovering from one of his many illnesses, is asked by the Bishop to stay in Santa Fe instead of going to the newly expanded regional area on mission, he is insistent that he go: “...down there it is work for the heart, for a particular sympathy, and none of our new priests understand those poor natures as I do. I have almost become a Mexican! I have learned to like chili colorado and mutton fat…I am their man!”

But Fr. Joseph was not always so convinced of his mission – not always so clear where he was being called. At two points in the story, Bishop Latour recalls his exchange with Fr. Joseph moments before they are set to depart on mission. Fr. Joseph is suffering for leaving his widowed father and is torn between the desire to go and the need to stay, but Fr. Latour helps him to take the decisive first step that leads to many more. Cather very tenderly insists that Fr. Joseph’s desire, manifested in that ‘yes’ and all the others, was not against his family – his biggest fear – even if it meant leaving them. His sister, who became a nun in France, received many letters from her brother. When Fr. Latour was visiting those French nuns, one reported to him that “after the Mother has read us one of those letters from her brother, I come and stand in this alcove and look up our little street with its one lamp, and just beyond the turn there is New Mexico.” In claiming Santa Fe for God, those priests belong to that place and those people, but the people, and even the topography of that new territory, now belong to everyone who meets them.

Ten years have passed since my first introduction to Fr. Jean and Fr. Joseph, and they have filled my heart with more Europeans than any Arkansas girl could have imagined. These years have made that initial perception of familiarity emerging from Cather’s pages clearer. That perception had less to do with specific faces, and more to do with Who those faces help me to see. Those missionary fathers (and mothers) help me to rediscover the meaning of my own history, of my own country, of my own way of speaking and being. They have become American – even more American than me! They have looked at my life and my history as Fr. Jean looked at his friend Jacinto’s: “a long tradition, a story of experience, which no language could translate to him”. They have helped me to become more myself by embracing me into the folds of a Tradition that preceded even them, inviting me to a life of mission that takes place around my dinner table and in my own family. My faith depends on these European missionaries, who come to offer the beauty they received and to find themselves in awe of all the beauty yet to be discovered. The life of mission hinges on us saying, along with Fr. Jean, “I do not see you as you really are, Joseph; I see you through my affection for you. The miracles of the Church seem to me to rest not so much upon faces or voices or healing power coming suddenly near to us from far off, but upon our perceptions being made finer, so that for a moment our eyes can see and our ears can hear what is there about us always.” In light of the recent School of Community work on Beginning Day, the bishop and his vicar are witnesses of mission, of bringing “this experience of the incarnation, of the humanity of Christ” within the reality they are called to live.