Book of the Month: A Quixotic Quest

An introduction to the November Book of the Month: The Relevance of the Stars by Msgr. AlbaceteAmong the many characters of film, TV, and literature that accompanied the life of Msgr. Lorenzo Albacete was Don Quixote, “Man of La Mancha.” I never spoke with him about the famous character, but I can imagine some reasons why Monsignor must have loved him and his story. First, there is the Spanish connection. Then, there is the character of Sancho Panza who shared Monsignor’s bodily proportions as well as his keenly realistic perspective on life. However, in the end, the main draw must have been the nature of the quixotic quest: ridiculous in the eyes of the world and of all the “sensible” people but animated nonetheless by a mad, overwhelming desire for something that plumbs the depths of reality in a way that the “sensibles” always miss.

All of that to say, I am embarking on my own (rather tiny) quixotic quest in writing the introduction to the Book of the Month, The Relevance of the Stars (Slant Books, 2021), by our beloved Msgr. Albacete. Partly because, if you pick up the book and open it to the normal place you find such things, you will find an introduction already written, by better writers, who knew Msgr. better than I did (in addition to curating the volume: thank you Lisa and Greg!). Additionally, the blurbs from the mighty figures on the back cover and first pages will probably do more for you by way of introduction to the book than all the words I could throw together. But the main reason my writing the introduction is quixotic is because I’ve never read it. To be totally accurate: I had read bits and pieces before, and then I read a good most of it while preparing to write this. I’ve read another book of Msgr. Albacete’s, God at the Ritz, more times than I can count and it seems that both volumes contain the veritable greatest hits of the Monsignor’s exceptional personal culture and interests (from Garcia Lorca’s snail to West Side Story, from physics to biology to biblical exegesis, from the Founding Fathers to Dostoevsky’s Ivan Karamazov, Mauriac and Wiesel, Pollack and Pera, Ratzinger, Von Balthasar, John Paul II, David Letterman, New Yorker cartoons, and mostly, Fr. Giussani). Actually, this is probably the perfect moment to add a plug for God at the Ritz, which I think could be successfully rebranded as The Relevance of the Stars for Dummies or even, The Religious Sense for People who Love Gas Station Chili Dogs.

Ultimately, I am unprepared and underqualified to write a proper introduction – the classic ingredients of quixotic delusion. But then there’s the other side of the coin when one is being quixotic: the outsized desire. When I was asked to write this intro, I immediately felt an outsized desire, which for me was to remember, to recall, to feel again what it felt like to be around Monsignor. It was like talking with him again, asking him my questions, lighting up another cigarette with him and just being “Mary-like” at his feet, spending time with him, listening to him speak. And so here I am again, glady remembering Monsignor. This strikes me as the main opportunity we have in the proposal of this book: containing his words, it provides a glimmer of the man, whose presence we miss and whose judgment on the world we still desperately need. I want to detail three such “glimmers” that caught my attention in reading The Relevance of the Stars.

1. It captures Monsignor’s gift for relationship and for friendship.

In every chapter, on every page, you sense a man who has no interest in issues or questions for their own sake. Although erudite – and extremely so in certain places (cf. “Learning to Say ‘I’” . . . try reading that one just once), it all has the tone of being addressed to another person. It’s conversational. I imagine some of these are sourced from his various “appearances,” as he used to call his speaking engagements. But no matter, even in the most complex parts, there is no philosophical dog chasing its theological tail. There is, instead, a man whose experience of communion and friendship has led him to deeply examine the conditions of the modern world and the salvific proposal of Jesus Christ in the Church. Far from stuffy meditations on hot topics, this collection has the warmth of his presence. You can feel the way Albacete would put you at ease and catch you off guard, while also experiencing his ability to plunge you so suddenly into the most profound things in human life.

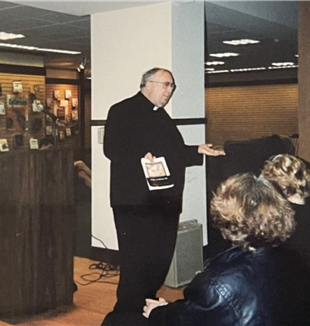

The only reason I really have anything to say about Monsignor is due to his particular gift for friendship. I met him almost 17 years ago to the date (November 10th), as a fairly awkward high school freshman. He was “appearing” at the DC area Beginning Day. I was playing guitar for the meeting and, as it happened, absolutely butchered every song, very obviously and very publically. I then had to sit in my front row seat the entire time, attempting to become invisible. After the talk and assembly were over, Monsignor made a beeline for me. He must be coming to shame me for the murder of Claudio Chieffo I just performed, I thought. Instead, he asked me if I was in a local rock band and, if so, was it increasing my luck in the lady department. I was shocked. We began to talk while slowly meandering over to Mass (very slowly: we arrived at the homily). In the hallway of the Maryland parochial school leading to the church was a series of computers. About 16 minutes into our relationship, Monsignor was already proposing a business venture where I steal the computers, he hears my confession, and we both profit off of their black market sale (he was obviously kidding). We sat in the back of the church; at the end of Mass, he grabbed a missal, ripped out a page and wrote down his phone number. Then he ripped out another page, handed me the fountain pen, and asked for mine. “They’ll think a little mouse got in,” he said to my shocked expression. We then went out for Peruvian chicken with the capi of the Communion and Liberation community in DC. While I’m sure they needed to speak with Monsignor about any number of things, I was the one that got to pull up a chair right next to him. At the end of that meal, he renamed me “Zaccheus.” That day, I was stuck in the tree of my own failure but the encounter with him forced me to come down from that tree (and then to dinner, as the story goes). From then on, our friendship continued with that same intensity. Pardon the lengthy anecdote – it is just to give a glimmer: he had a capacity for relationship that was extraordinary. And it shines through these writings clearly.

2. It captures Monsignor’s fierce passion for the human and the human’s heart.

The heart is the refrain of the book. It was the refrain of his life: to live out for himself and then to reinterpret for us, through his humor, his thinking, and his friendship, the teaching of Fr. Giussani about the heart and its infinite desires. There is not a chapter in the book where he does not remind us, since we forget all too often, the definition of the heart. Understanding the heart formed and informed the way Monsignor thought about everything. Because firstly, it informed the way he lived. He was serious about his desire. Among the most banal but poignant examples of this were his public smoking episodes, especially those in which the locale explicitly banned smoking. Going back to the story of before, I myself even saw him light a cigarette in that Peruvian chicken restaurant in Wheaton, MD. He was sitting in direct sight of the “No Smoking” sign and almost finished his cigarette if only because the staff was so shocked that he was doing it in the first place. And as much as he enjoyed it, smoking was towards the bottom of the pile of the objects on the receiving end of that desire to which he was so loyal.

Faithfulness to our infinite desire is the proposal for living out all of the “problems” addressed in the book: from love and affection in “The Lovers and the Stars,” to the state of modern Christianity in “The Church of the Infinitely Fractured,” to the beautiful and insightful (and sorely, sorely needed) chapters on America, to political questions, scientific questions, the question of secularism, medicine, culture, investing…hell, even what it means to be a Catholic lawyer. The answer lies in the heart. And not merely in the definition of the heart; the answer is in actually living out a bold and fierce fidelity to those desires so that they can inform every facet of life, as they did for Monsignor.

3. It captures Monsignor’s totalizing knowledge and love of Christ.

Monsignor identified easily with the “searchers” of the world, in all the forms they came in, from Christopher Hitchens to the “crooks but nice ones” (his words) who sold him used cars in Washington, D.C. He loved those who were “on to something,” as Walker Percy would say, those on the hunt for the “Mystery.” However, I believe that Monsignor was a “searcher” in a crucially different way. In 2013, I wrote him this email: “When we say ‘the Mystery’ and when we say ‘Jesus of Nazareth,’ are we speaking of the same thing? Because there is an experience in front of which it seems more true to identify the Mystery at work because of the grandeur, the incomprehensibility, the (obvious) mystery of it...but there are other times when it is so clear that calling out ‘Jesus’ is true, someone that is simple, tender, loving. How can these be the same thing?” And he responded: “Jesus is the REVELATION of the Mystery in human form, like we are. The point is that He reveals the Mystery to be Love. In Him, in His Love.”

This is the difference. Monsignor wasn’t just someone searching for the Mystery; he was one of the little ones of Christ, whose belonging to Him gave him all of the liberty that St. Paul spoke about. It was a liberty that allowed him to explore the world passionately, to ask the questions he had insistently, even to cry out demandingly in his pain and suffering. Just like a child. The searching of the world, while so beautiful and, at its core, good, has no banks to direct its energy. Monsignor’s searching was within the banks his relationship with Christ, and, therefore, within the Church. That is what made it a raging river and not just so much diffuse water.

He loved Christ; he was enamored of Him. He was on a first name basis with him: Jeeeeeeeeeeeesus, as he used to say in his best Southern Baptist preacher drawl. And if every page of this book elucidates the nature of our heart as I said above, it is because every page of this book arises from the depths of his childlike relationship with Jesus.

If you never knew Monsignor Albacete, this book can be a great start (but also check out God at the Ritz and the various Youtube relics of his “appearances”). And if you did know him, as so many of us did, let this Book of the Month be an occasion to consult him again, bringing your questions, your concerns, all of your humanity. May it be an occasion to sit with him again, with the Panda Show, the Mystery’s best spokesman, the poor fool of Christ, the Mystical Monsignor, Lorenzo, our friend and our companion – little, quixotic snails though we all are in this great forest of life – on our journey toward and among the stars.