Affirming the Genuine Aims of Life

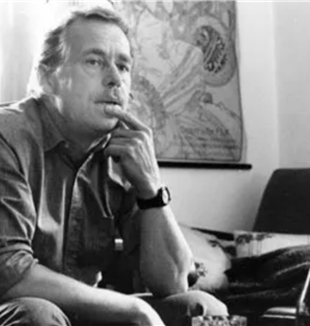

For September’s Book of the Month, we propose again Vaclav Havel’s The Power of the PowerlessVaclav Havel wrote The Power of the Powerless in 1978, ten years after the Warsaw Pact armed forces came into Czechoslovakia to clamp down on the nation as it was demonstrating a troublesome penchant for a democratic socialism that was unacceptable to the communist party’s doctrine. In 1968, Havel was a thirty-year-old playwright developing a reputation for absurdist plays that criticized the communist regime. Because he came from a wealthy background, he had always been a persona non grata in the communist state, but outside of his plays, he had not been politically active. As the party tightened its grip after 1968, Havel was banned from participating in the theater in his native land. He continued writing plays, now bolder ones distributed and performed in underground cultural venues. Havel also became directly involved in political activity. He was a leading figure in the promulgation of Charter 77, a 1977 manifesto that demanded a respect for human rights such as freedom of speech. It was signed by hundreds of prominent figures in society. The government cracked down harshly on the authors and signatories. There were arrests, brutal interrogations, and many lost their jobs. Havel was arrested, interrogated and put under surveillance by secret police. It was in this climate that he wrote his famous tract, The Power of the Powerless. It was intended to be part of a dialogue with Polish dissidents, although that never materialized. Havel was soon to be imprisoned for four years by communist authorities.

The most striking aspect of Havel’s essay is that, although it is often described as a classic text of the dissident literature of eastern Europe in the days of communist domination, he makes it clear that he does not seek to be a dissident at all. As he writes:

“… if living within the truth is an elementary starting point for every attempt made by people to oppose the alienating pressure of the system, if it is the only meaningful basis of any independent act of political import, and if, ultimately, it is also the most intrinsic existential source of the ‘dissident’ attitude, then it is difficult to imagine that even manifest "dissent" could have any other basis than the service of truth, the truthful life, and the attempt to make room for the genuine aims of life.”

Havel insists throughout this essay that it is almost futile to keep the focus on the system, analyzing its weaknesses and planning its demise. We can begin in the present moment simply by living the truth, affirming “the genuine aims of life,” uncorrupted by the suffocating state-imposed ideology. The challenge to the state that he proposes is the challenge of people refusing to be something other than authentic human beings. To illustrate this point, he gives the example of the grocer who must place a “Workers of the World Unite” poster in his store. This statement means nothing to him. He would not choose to make this statement of his own accord, but he is afraid not to make it. It is not an expression of his views, but a signal to his boss and the higher-ups that he is in step. It pleases the higher-ups, who might have no regard for the slogan either, but their comfortable existence could be jeopardized by non-compliance on their watch. Truth becomes lost in a growing mist of dishonesty and people are separated from themselves. The day the grocer decides that he will not put up the poster because it means nothing to him is the first step toward a new order.

For Havel, it is this small-scale affirmation of real human needs that will triumph in time. He is a humanist of the highest degree, possessing a faith in the beauty and power of the human heart to transform society, one day at a time, one circumstance at a time, one affirmation of an actual truth at a time. He had faith that an authentically human political order would eventually arise as a consequence of human beings who chose to live in an authentic way. An attractive feature of his vision is that it waits on nothing. It is not a counter-utopian vision to the communist vision. One does not need to seize political power to violently bring it into being. One may this very day simply have the courage to speak and act from his or her own heart, and not at the behest of those in power.

For us in America, this essay is valuable. I grew up during the Cold War and believed firmly that our nation represented a respect for human rights and freedom of speech. Our adversaries, the communists, were the problem on that score. The Soviet Union has long since collapsed, but within our nation a totalitarian tendency has grown as political factions seek to suppress dissent and mandate public assent to cultural positions. Arguments are not won; ideas are simply banned. There are things one must not say because it offends those in power.

Our tendency in front of this political and cultural moment is to begin looking for the levers of power – to find some way to grab the power and turn the threat on its head. In this way, we can often become what we oppose: dictatorial, intolerant, and violent. The value of reading Havel’s essay is the reminder that the more human world we desire to see has to begin with our desire to be more human this very day. Political response is of course necessary, but our response, political or that of daily human struggles, has to be informed by a desire to live and offer a full, authentic humanity, not a reaction driven by fear or anger. I am grateful for Havel’s reminder that this does not have to wait for any other development at all.