"It’s up to the life in you"

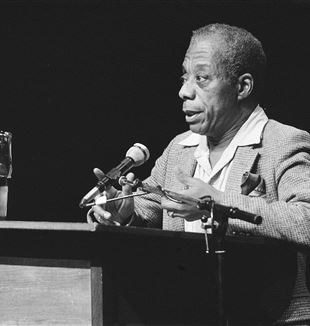

The American writer James Baldwin, among the most powerful of the twentieth century, was the conscience of his time. Originally published in the July-August issue of Tracce.Originally published in the July-August issue of Tracce.

Adapted from articles previously published in Faithfully and America Magazine.

I first discovered James Baldwin one summer night as I was perusing Netflix. The provocative title “I Am Not Your Negro” caught my eye. The documentary displayed a compilation of film clips, footage from the Civil Rights era, and interviews with Baldwin, interspersed with voice-overs by Samuel L. Jackson of some of Baldwin’s writings.

Some Civil Rights activists approached racism as a political problem to be fixed primarily by policy changes. But for Baldwin, racism was a human problem, which he allowed to pierce the depths of his heart. This pain generated in him a set of personal, or existential questions about the nature of man and about his own identity: How is it possible for such acts of evil to be perpetrated by other human beings? How could people be so blinded to the humanity of their brothers and sisters? Instead of settling for sentimental or ideological answers, Baldwin dedicated himself to these questions, letting them become the catalyst for a life-long journey.

I was immediately reminded of what happened when I was taught about the Civil Rights movement and the life of Martin Luther King Jr. when I was in second grade. I remember feeling baffled the day we learned about King’s assassination, and I couldn’t sleep that night because of how much I was crying. My mother walked in and asked me what happened. “I don’t understand how they could do that to him? How could people do something so evil to someone so good?” I went to class the next day, hoping my teacher could help me understand this better. She answered by saying, “well, it’s because racism has been a part of our country for so long. This is why we have to fight for a more just society.”

She didn’t seem to grasp the nature of my question. I understood why James Earl Ray shot him. I understood that the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow made some Americans feel threatened by the idea that black people should have the same rights as everyone else. I realized that what I was trying to understand is the phenomenon of evil in itself. Why did it exist at all? And where did it come from? When my teacher realized that my question was more existential in nature, she responded by saying “we can’t really know the answers to those kinds of questions. We just have to try to make the world a better place…” Such a dismissive answer didn’t satisfy me, nor would it have seemed to satisfy Baldwin.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Baldwin was born in Harlem, New York in 1924, growing up at the tail end of the period of artistic revival known as the Harlem Renaissance, and at the beginning of the Great Depression. He was raised by his mother and stepfather, having never known his birth father. His stepfather was a fiercely devout Pentecostal, and struggled with mental health issues, which at times caused him to lash out violently toward his stepson. Baldwin described his loathing when looking upon him dead in his casket and how unsettled this hatred made him.

In his essay “Notes of a Native Son,” James Baldwin compares his experience as an unloved stepson with his experience as a black American, noting that U.S. culture treats blacks like ugly stepchildren. The most alarming experience of racism he had was in a diner in New Jersey in 1948. He recounted a surge of rage taking over him as the waitress told him, “We don’t serve Negroes here.” He started to lose awareness of what was going on and ended up flinging a glass at her. She ducked, and it shattered a mirror on the wall across from him. As he regained consciousness and bolted out of the diner, he writes that he “saw nothing very clearly but I did see this: that my life, my real life, was in danger, and not from anything other people might do but from the hatred I carried in my own heart.”

Baldwin felt this kind of hatred not just for white racists, but for his own stepfather. Baldwin eventually went on to become one of the most powerful voices in 20th-century American literature. His work touched on issues like sexuality, race and class in ways that were far ahead of his time. As a young man, increasingly able to recognize the correlation between the wounds inflicted by his stepfather and by racist America, Baldwin grew in his determination to fight against injustice and hatred in all of its forms.

“This fight begins, however, in the heart,” he wrote, “and it now had been laid to my charge to keep my own heart free of hatred and despair.” The idea of covering over his wounds by hating his actual stepfather or racist U.S. culture would not satisfy him. He knew that to be truly free meant to be healed.

Baldwin’s wounded relationship with his stepfather made him desperate to find role models and mentors as he was growing up. The most impressive one, perhaps, was Beauford Delaney, whom he met in Greenwich Village in 1940. Baldwin was immediately captivated by his warmth, charisma and artistic vision. One of the most striking memories Baldwin had of Delaney was of when they were walking down the street after a rainstorm and Delaney pointed out a puddle, asking him to “look.” Baldwin claimed to see nothing but water. Then Delaney asked him to look again. This time, Baldwin noticed some pools of oil swirling within the water, causing the reflection of the buildings to radiate brightly.

He experienced Delaney to be his “long-lost father” who “never gave [him] any lectures” but instead provoked him to recognize beauty within the ugliness, both internally and in the world around him. Baldwin learned to look at reality through his mentor’s gaze, going on to say that “the reality of his seeing caused me to begin to see.” In his 1964 essay Nothing Personal, a monograph that included photographs by Richard Avedon, Baldwin spoke of the “miracle of love” that begins to “take flesh” when we encounter someone who embraces our wounds and is unafraid of making themselves vulnerable to us. Delaney was not the miracle but instead helped Baldwin to be more receptive to that miracle, wherever it might come from.

Many of Baldwin’s realizations and much of the language he used are rooted in his Pentecostal upbringing. He distanced himself from the church of his childhood (and from organized religion in general) because of its moralistic and pietistic nature. He also struggled to reconcile his homoerotic tendencies with the biblical precepts on sexual morality. Yet he retained a strong awareness of his “structural” need for God, as Giussani put it when referencing a dialogue from Baldwin’s Blues for Mister Charlie in chapter 5 of The Religious Sense:

RICHARD: You know I don’t believe in God, Grandmama.

MOTHER: You don’t know what you talking about. Ain’t no way possible for you not to believe in God. It ain’t up to you.

RICHARD: Who’s it up to then?

MOTHER: It’s up to the life in you - the life in you. That knows where it comes from, that believes in God.

Ironically, it was by leaving the church that he was able to come to understand his need for salvation, for a “revealed” answer to his questions. Baldwin was also helped to judge his experience as an American by leaving the country. His years spent in France beginning in 1948 afforded him the clarity to make sense of both the greatness and errors that are particular to his own culture.

Baldwin’s faithfulness to going to the depth of his wounded humanity enabled him to recognize his need for a greater love, for a truer happiness. He allowed the evil of lynchings, segregation, and hatred to provoke him with a sense of awe. As much as he valued those who made efforts to correct the systemic origins of social injustices inflicted on Black Americans, he understood that addressing the moral evil of racism was not just as a problem to be fixed, but a question to be lived.

Though it is 37 years since Baldwin’s passing, his work continues to be all-the-more relevant today. Baldwin is challenging to read. He often indicated that his intention was to shake up white people’s complacency. I recommend that we look to Baldwin’s life and works during these divided times, not necessarily because I agree with every conclusion he comes to (I don’t), but because he asks incisive, important, if not crucial, questions that we all need to face.

Baldwin had the ability to go back to basics and face what is most fundamental about the human experience. His profound yet universal questions are capable of crossing through ideological divides, and have the potential to initiate a common journey that invites all humans—black and white, left and right, atheist and religious—to go deeper into our experience and look more closely at reality.