Never Give Up Asking

Part II of The Religious Sense at Work Series: the witness of a stay-at-home momThe Religious Sense at Work is a weekly limited series that explores the way our communal reading of The Religious Sense informs and illuminates our experience of work.

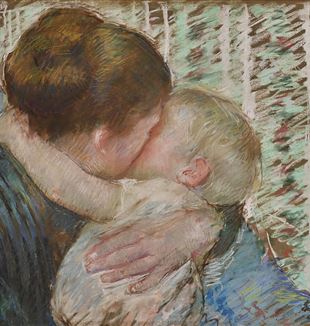

No experience in my life has stripped me down to my limits like that of motherhood. Each day brings new reminders of how powerless I am. I cannot control my children or what evils that may befall them; the demands on my time and capacity far outweigh my ability; and my desires for myself and my kids (for example, interesting activities to propose to them, hobbies I want to explore, people and places we want to visit) often go unmet in exchange for a much-needed nap time or a bathroom disaster clean-up.

I can observe each of Fr. Giussani’s reductions in chapters 6 & 7 of The Religious Sense at play on a micro-level in myself almost daily. I think the one that stay-at-home-moms (especially myself) are most often tempted by is that of “the practical denial of the questions.” Not only are the questions painful, but who has the time and energy to reflect on the meaning of life when you are waking up with a baby three times a night or driving from school, soccer, swimming lessons, etc.? The colloquial phrase for this might be “survival mode,” and moms often become dominated by it.

In fact, us moms have a tendency to encourage each other in this way under the guise of being “supportive.” The tamping down of personal responsibility (which is an easy attitude to take on when the link between “my path as a person and the destiny of the world” is lost) means that I do what I need to do just to get by, with no need to apologize, and no need to seek out anything more than that.

The result of being dominated by survival mode for me is quite simply boredom. The days droll on in an endless cycle of nursing, diapers, stroller walks, preschool pickup, play dates, nap time, snacks, dishes, and so much laundry. And at the end of the day I end up irritated and plagued with feelings of guilt that I should be enjoying every moment because “it goes by so fast.” Ultimately, underneath the guilt and exhaustion, is a lack of awareness that any of those tasks have any meaning beyond the immediate results they yield.

Society often praises moms as having “the most important job in the world,” and while these cliches may be well-intentioned, the implication is that the meaning of my work as a mother lies in the “product” of my work — that is, well-adjusted happy adult leaders and the problem-solvers of the future. This sounds like a worthy goal, but even if I could know for certain that my children would be virtuous model citizens (which, by the way, is never guaranteed), that fact would not give me comfort during a 3am feeding. My need for meaning is not fulfilled by a future promise, no matter how noble. In that way, I deeply relate to Dostoevsky’s position as quoted by Fr. Giussani: “…if it all happens without me, it will be too unfair.” What gives meaning to my daily work as a mother is not, ironically, my children, but an event that embraces each menial task as a step toward my own destiny and, mysteriously, that of the whole world.

What then can help me rediscover my own desire? That is, what helps me live out my religious sense in the context of motherhood? Shaking off “survival mode” and seeking out experiences and encounters that broaden my desire. Staying with other moms and families who share this desire is a great help, but that isn’t always possible. Thankfully, reality provides plenty of opportunities: preparing “meal train” dinners for new moms or families in need; participating in our local Well-Read Mom book club; proposing interesting activities with the kids; inviting the neighbor to dinner; and prioritizing attending School of Community (even though getting out the door in time seems impossible).

These things aren’t more meaningful than my tasks; rather I seek them out because they help sharpen my awareness of the great meaning in my tasks of motherhood. This is the “event that overcomes the limits of our existential experience, of the now” (p. 79). The answer isn’t doing more (because sometimes it really isn’t possible, and even when it is, there’s always the danger of total chaos and/or failure), but looking up and turning my gaze toward people and places where something new might emerge. When I follow my interests and desires, which is always a sacrifice and always a risk, I rediscover my own religious sense alive and well.

Finally, I learn much about the religious sense from my children, who always wear their desire on their sleeve. They are never afraid to ask (even if it means candy for breakfast), and certainly never give up until they are answered. From them I learn to turn each day to the Father and ask for everything, which He gladly gives.

Meghan, Nashville, TN