A Beggar in Radical Imitation of Christ

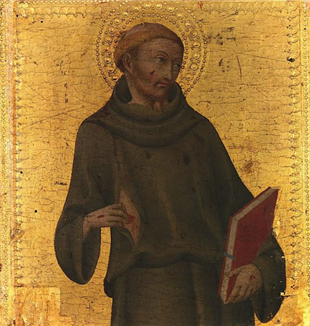

February’s book of the month: St. Francis of Assisi by G.K. ChestertonIn St. Francis of Assisi, G.K. Chesterton offers us a sketch of one of the wildest and most beloved figures of Christian history. A young dandy from a comfortable perch in the society of Assisi, Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone was nicknamed Francesco (“Frenchie”) for his love of French poetry and fashion. Quite unexpectedly for his family, Francis abandoned all comforts to live like a beggar in radical imitation of Christ. His choices lit a flame in the hearts of thousands of men and women throughout Europe, generating a movement of Christian life that continues today as the largest religious order in the Catholic Church, present in over 100 countries.

Chesterton devotes some of his initial reflections to the difficulties of writing about such a subject. Francis, unlike many prominent figures in Christian history, had many admirers in the secular English culture of Chesterton’s time (late 19th and early 20th century). His abandonment of wealth and his love of the poor was appealing to socialists, who saw in him a subversive figure, shaming the property-owning classes. Francis can properly be seen as an engine driving the great artistic achievements that followed in his wake. His inspiration is felt strongly in the poetry of Dante and the painting of Giotto. His miracle plays contributed to the development of modern theater. His astounding voyage to end the Crusades by speaking with the Sultan is an inspiration to pacifists. So, it is possible to see him as a remarkable man clothed in the regrettable superstitions of the day, but remarkable just the same. According to Chesterton, this attempt to tell the story of a saint without speaking of God would be like talking about Robert Peary’s life and say nothing about the voyage to the north pole. That voyage was at the core of his life.

Likewise, an attempt to begin with the miraculous events of his life and the expressions of piety that Francis lived and passed on would make him incomprehensible to many in the modern audience. It would furthermore run the risk of a certain presumption even for believers who admire his piety. It would require a saint to fully enter into the realm of his sanctity and unpack it for all of us outside. The best route for Chesterton, therefore, is to adopt the posture of a sympathetic, open-minded outsider. His goal is to attempt to take on the entire phenomenon of Francis, without reductions or preconceptions. His invitation is: “Let’s stand in front of it, censuring nothing and see what we make of it.“ This posture, accompanied by Chesterton’s undeniable wit and eloquence, makes for an enjoyable reading experience, not because it is a systematic walk-through, but because you are witnessing and participating in Chesterton's own discovery of this man.

Chesterton was an artist at heart and a journalist by trade and it is helpful to keep these two characterizations in mind to appreciate how he operates. He was studying art before he shifted to a career in journalism and an outstanding trait of his writing is his artist-like intuition. Chesterton has an uncanny ability to grasp the heart of the matter quickly and this makes his more particular observations all the more insightful. As a journalist, Chesterton was deeply engaged with his cultural moment and his audience was the common, skeptical newspaper reader. He was a genial polemicist who sought to open the eyes of his contemporaries to the deeper truths that his intuition illuminated by asking the reader awkward questions about the unexamined assumptions of the educated class. His journalistic vein never caused him to be submerged in his moment. He was a writer who continually sought to open his moment up to the eternal truths that were nestled obscurely in the dim core of the question at hand. The journalist and the artist work together nicely in St. Francis of Assisi.

There are many gems in this book. Many stale assumptions of Chesterton’s own time are still thriving today, often inside of us. As a sharp-witted journalist observer, he helps us to pluck away these styes that hinder our vision often with his brilliant paradoxical one-liners. Chesterton employs his intuitive gifts to grasp the whole – the essential Francis. He wishes to help us look with fresh innocent eyes on a remarkable man and be moved by the saint’s life all over again. From that, one can explore more deeply or perhaps be moved to humbly ask God, with fear and trembling, for the gift of sanctity.